Interview with Lorraine Price: Director of Short Film “The Hairdresser”

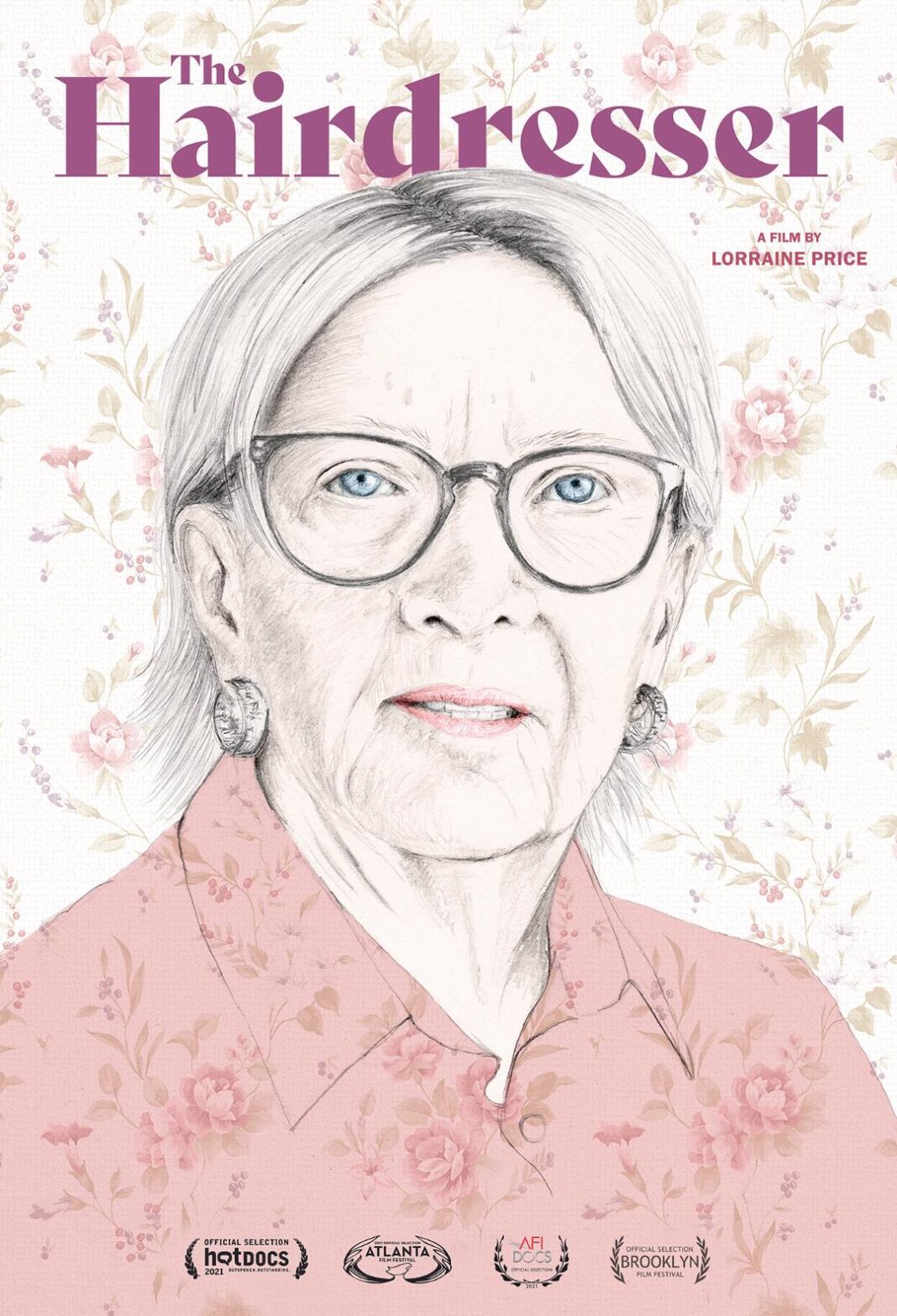

The Hairdresser (La Coffieuse) is a short film by Lorraine Price that shares the story of an 83-year-old woman who does hair for terminally ill patients. Premiering at the 2021 Hot Docs International Film Festival, it received an honorable mention for Best Canadian Short and second place in shorts for Audience Choice Awards.

In this interview, filmmaker Lorraine Price sheds some light on the process of creating her first short, and her perspective on The Hairdresser’s unique story.

CB: You have said that you have always wanted to be a storyteller. What has inspired you, and how did you get into directing and visual art?

LP: I have wanted to be a storyteller since I was really young. I remember telling my mom when I was seven that I was going to be a writer. I didn’t really understand at that point that people made films, they always just kind of appeared, but I did understand that people wrote books. So, I went to school for creative writing and English literature and got joint honors for both from Concordia University in Montreal. I had sort of flirted with film throughout my time at university. I would take a film class here and there and always loved them, but I ended up focusing on my existing degree. I did my masters in literary translation, and while I was completing my master’s program, I started training as an amateur boxer in Montreal. So, I was training a lot and participating in fights. After I had about nine fights, I ended up getting pregnant and I couldn’t box anymore, but I didn’t want to give up this relationship to the community that I had formed.

Women’s boxing was going to be included in the Olympics for the first time ever in 2012, and there were a lot of really great stories around that event. One in particular was playing out in Canada between two best friends and two of the best boxers in the world, and I thought it would make a great documentary. So, if I wasn’t going to box, I was going to try and tell a story about that community. I found a co-director, Juliet Lammers, here in Montreal and we started to pursue our first feature documentary film!

CB: The Hairdresser is credited to your grandmother. What is her influence on the project?

LP: My grandma, she was always a really loud and ostentatious dresser. She dyed her hair fire engine red and wear bright red lipstick to match. Custom jewelry, floral print blouses, platform shoes—she was just a very loud dresser. It was a huge part of her identity. When she passed away, her hair was short and white, her lips were pale, her nails were nude, and in so many ways, she just looked like a shell of the woman that I had known. It hurt me, but it didn’t surprise me because it was what I had come to expect from someone who was nearing the end of their life. But it struck me, and after she passed away, I came back to Montreal, and I read a little article in a local newspaper. It talked about Kathleen’s work at as a hairdresser at the palliative care unit at a hospital here in Montreal. She’d go in every week and wash their hair, do their hair, and their makeup if they wanted. When I read about her work it just transformed my understanding of end-of-life care. I was very concerned with my grandmother’s comfort and her suffering at the end of her life, but I never thought to paint her nails, or wash her hair, or put on some lipstick—things that had been so important to her for her whole life. So, I wanted to make a film about Kathleen and her work because I felt like maybe if there weren’t so much taboo around death and dying and we spoke more openly about what we can do for each other, maybe I would have thought to do that for her.

CB: How did you assemble your crew for The Hairdresser? (Cinematographer Jacqueline Mills and Editor Pauline Decroix)

LP: I’ve made a couple of sports documentaries about women athletes. My first one was about women boxers, and my second was about the rivalry between the American and Canadian women’s hockey teams. Pauline was the editor on my hockey-doc called “On the Line”. While we were working on that project, I told her about this one, The Hairdresser, and she talked to me about her experience with a friend who had passed away in palliative care. She had a really personal connection to the subject matter that I felt was important, and we had worked together before and had a really great creative collaboration, so that’s why Pauline came on board. She’s also just a very sensitive soul, and I felt like this project needed somebody who is comfortable with death and thinking about death, and because she had confronted that in her personal life, I felt like she was a good choice.

My cinematographer Jacqueline Mills is an East Coast filmmaker but has been based in Montreal for several years. She made a film called “In the Waves” that came out several years ago, and I loved that movie. I loved the way it was shot, I love her eye, the way that her camera is so gentle and floats around the people she’s shooting. It’s really immersive without feeling intrusive, and I just really appreciated her cinematography. She’s also a director herself, and because we were going to be shooting in palliative care, which is a very sensitive environment, I needed a very tiny crew. I needed it to be just me and my cinematographer, and I was going to be on sound while my DP would be pretty independent with the camera. I wasn’t going to be looking over their shoulder, I wasn’t going to be able to whisper to them about the frame, or the timing, so when we were shooting, I needed them to be able to think like a director, and Jackie is the perfect choice. She’s really a gifted cinematographer with ridiculous emotional intelligence, and she could be in that room and think both like a DP and a director, which is exactly what I needed.

CB: Tell me about your experience filming and working with Kathleen, Jacqueline, and the hospital patients all at once. Did you face any challenges?

LP: The film took four years to make. When I started it, I reached out to Kathleen first and she put me in touch with the foundation that runs the palliative care unit. I went in to meet with them and told them my personal story and why I felt like it was important to make this film, and they came on board right away. Then it was just a matter of me jumping through all the hoops in terms of hospital administration to get permission. That worked out…and then then the hospital administration changed. I lost my access, then I had to work to get it back, and while I was working to get the access back the palliative care unit moved. It was a long, complicated move as these institutional moves tend to be, so that really delayed the project. But over the course of those four years, I would take my zoom recorder and my lav and I would just go sit in Kathleen’s living room on her couch and we would have tea and talk. They weren’t formal interviews, it was just really conversation between her and I, I had never prepared any questions. I had things I was curious to talk to her about, but it was really casual. All of the voiceover in the film is from those couch conversations that we had.

At the end of four years, I did two shoots in the Fall of 2019. I had more shoots planned for the Spring of 2020, but COVID happened and that was the end of that…because it was a hospital, and Kathleen’s 83, and the patients were terminally ill…it just became very clear very quickly that it was not going to happen.

The initial idea for the film was to do several patients, but the universe just had other plans. But after Madame Lalonde accepted to be in the film, it turned out that it was her film. It belonged to her and Kathleen and their moment together, and it was a better film for it.

CB: What were some of your main takeaways from filming The Hairdresser? What do you hope your audience comes away with?

LP: It probably relates back to my own relationship to my grandmother and her death. I think that this film was about as close as I could get to an apology from me to her for not thinking of doing those things for her. I was just so caught up in “is she suffering” and “is she in pain” and “does she recognize me” and “what can I say that will give her permission to leave if that’s what she wants to do”… and those are important things! Don’t get me wrong, those are really important things…but I think I forgot that she wasn’t gone yet. She was still there, and there was still a way for me to honor her life and who she was.

I would hope that this film will make people think a little bit differently about what they can do for their loved ones when they are faced with the end of their lives and their stories. Something that seems so small could still be so meaningful, and sometimes we forget.

CB: With regards to the state of diversity in the filmmaking industry, what are your thoughts and hopes for the future? How do you play a role?

LP: I just want more films that highlight BIPOC filmmakers, and more stories about gender nonconforming individuals. I want more stories that center women’s voices and their experiences—women that are all ages, shapes, and sizes. I’m really excited by what I’m watching right now, and I feel inspired and lucky to be making and watching films at this particular moment because it’s just the beginning; we’re just beginning to see all of the perspectives and experiences that we haven’t been seeing on the screen for so long. There’s so many and it’s so much better this way—it’s so much more interesting! I’m lucky enough to be in this industry when the tide is finally turning. I hope that this tide is just unstoppable—I hope that there’s nothing that anyone can do to stop it and it’s just a runaway train. My dream would be an extension of that. Diversity and equality both in front and behind the camera should be the norm. I certainly thought about that when I grew up, and when I’m looking for a technical position, I really like to work with women and pay it forward—because if I’m lucky enough to be doing this and climbing the ladder in my own career, I want to bring other women up that ladder with me so that we can rise together.

CB: Do you have any plans for future projects?

LP: I’m working on another more personal project now that’s about my grandmother’s life in more detail. It’s a documentary about my family and my grandmother, and it’s a docu-fiction hybrid. All these creative nonfiction films have been at the forefront of my mind, I’ve been watching more of them these days and thinking about them a lot. That film is also a participatory doc, so I’m in the film, which means I have to rethink the way that I make it. I’ve never made a participatory doc before, so there’s a real shift, but I’m really excited about it. I’m also working on my first fiction film! It sort of grew out of The Hairdresser and also centers around the question of dying with dignity.